This essay originally appeared in Imago #1 (August 2021), the non-fiction/theory print annual published by the Locust Arts & Letters Collective.

WHEN WE started Locust Review (LR) in 2019 as a quarterly cultural journal of critical irrealism, we had two main antagonists in mind. We were in opposition to what Mark Fisher calls capitalist realism; the idea, as Fisher describes it, that in neoliberal capitalism nothing at large can be imagined — culturally or politically — that doesn’t fit into the overall logic of capital accumulation. [1] We argued the stultifying anti-imagination of capitalist realism had infected every aspect of social being; producing in daily life, in the “art world,” and in popular culture, an empty empiricism and cynicism. This realism often served to re-articulate the traumas of the exploited and oppressed, potentially turning images, for example, of police violence into disciplinary images. We were also alarmed by a growing fascist irrealism -- for example in the Alternative Reality Game (ARG)/conspiracy theory, QAnon. We sought to help construct, to borrow from André Breton, a left counter-mythology to this far-right threat. Further, we argued that capitalist realism, like neoliberalism more generally, was enabling the growth of fascism. [2]

Irrealism, as articulated by Michael Löwy, is a category of cultural gestures, artifacts, and media that rejects or moves beyond realism: this includes speculative fiction, surrealism, mythology, occultism, magical realism, science fiction (SF), and other non-realist genres, forms, approaches, tropes, etc. Critical irrealism refers specifically to those irreal artifacts and gestures that use their otherworldly or irreal character in a way that aims to criticize accepted “reality.” [3] While there is an ideologically centrist (or neoliberal) irrealism, its left and right poles are contested between critical irrealism (on the left) and fascist occultism (on the right). As the neoliberal political center falters, as it has with the election of Donald Trump, the rise of Le Pen in France, and the Modi government in India, there is a competition between the far left and far right in articulating a radical response -- politically and culturally -- to the failing capitalist realism of the political center.

LR roots this analysis in the phenomenology of the subject and the experience of individual exploited and oppressed persons living in a declining racist empire on the verge of climate catastrophe. There is a radically democratic aspect to critical irrealism, but there is also a mass character to fascist occultism. In the context of capitalist realism, the non-ruling-class subject is ultimately compelled to imagine new worlds; compelled by the intolerability of everyday life. In this way, capitalist realism, like other capitalist ideologies, contains the seed of its own destruction. If the working-class is, as Marx argued, the gravedigger of capitalism, [4] and each individual gravedigger is engaged in their own universe-building, socialist culture (anti-capitalist democratic culture) represents a gravedigger’s multiverse. [5] But this isn’t the only possibility. There is another cultural response to the “intolerability of daily life” — fascist occultism. [6] While the critical irrealist ties the emancipation of the constrained subject to a collective fight against the forces that constrain that subject, the fascist occultist seeks unity with the constraining forces. Each responds to the disfigurement of individual subjectivity under the “normal” workings of capitalism; each rejects, to some degree, the profound lack of imagination engendered by capitalist realism. How they are opposed, in irrealist cultural performances, gestures, artifacts and media, is largely in the different ways they position/construct/code subjectivity in relation to the sources of this disfigurement.

What do We Mean by Fascism?

Our approach to fascism is a modified understanding of the classical analyses put forward by historic figures like Leon Trotsky, Antonio Gramsci, and other Marxists. [7] Fascism is not a phase of capitalism; or a teleological outgrowth of capitalist relations. Nor does it simply refer to a particular kind of government, or a quantitative tally of its barbarisms. The death tolls of various “democracies” easily rival that of certain fascist states. Fascism is a process by which middle-class and other social layers are militarized along reactionary lines and progressively fused with parts of the state — forming fascia — in response to some kind of crisis that cannot be ameliorated by the normal workings of bourgeois democracy. For this movement/process to become a government a certain level of crisis and fascia development must be reached, and the fascia must garner support from significant sections of the capitalist class. Moreover, the character of each national fascism corresponds to the specifics of each country and the specific crises that produce it. Fascism in the United States, for example, invokes slogans of “liberty” and “freedom” in a manner that would be alien to certain European fascists. As I have written elsewhere, the “liberty” of US fascism is the liberty of plantation owners. The “freedom” of US fascism is the freedom of the settlers who stole Native lands. [8] Fascism is, first and foremost, a possible and contingent byproduct of capitalism’s periodic crises.

Against Adorno’s “Theses Against Occultism”

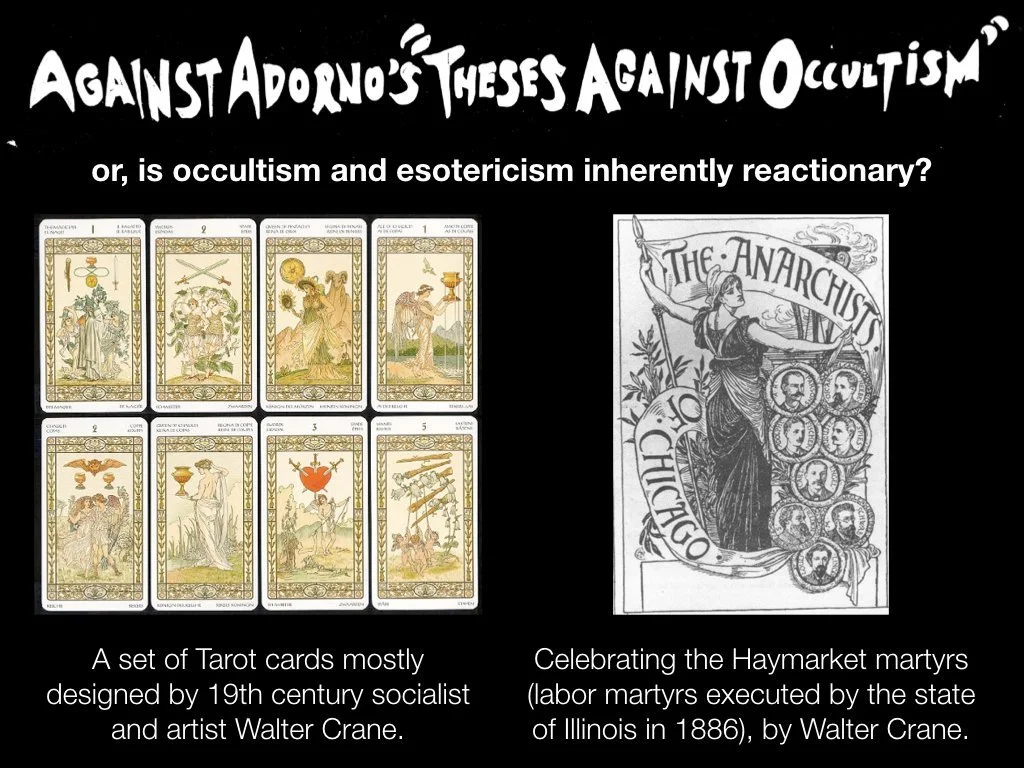

The primary error that Marxists have made when approaching the political character of irrealist artifacts is a kind of genre essentialism; assuming that certain irreal genres or forms are inherently or essentially progressive or reactionary, often basing this assessment on a positivistic bias toward the scientific, frequently connected to a crude teleology of progress. In doing so these comrades and scholars have dislocated both a central agent of cultural praxis — the artist — and the central agent of Marxist praxis — the worker. These scholars generally do not even consider the substantial overlap in these categories; the worker as artist or cultural agent. Because occultist practices are constructed by variable social actors, with variable interests and variable class-positions, occultist and esoteric cultural artifacts are contested between left, right, and the everyday common-sense ideology of capitalism.

In his “Theses Against Occultism,” Adorno argues the esoteric and occult are products of a decadent capitalism and are objectively reactionary. To make this argument, Adorno positions the occult against a Hegelian teleology of reason, [9] flattens or ignores the contested history of actual occultist and esoteric culture, [10] and relegates the cultural subject — artist, worker, or both — to a passive vehicle for an abstract rationality or abstract irrationality. [11]

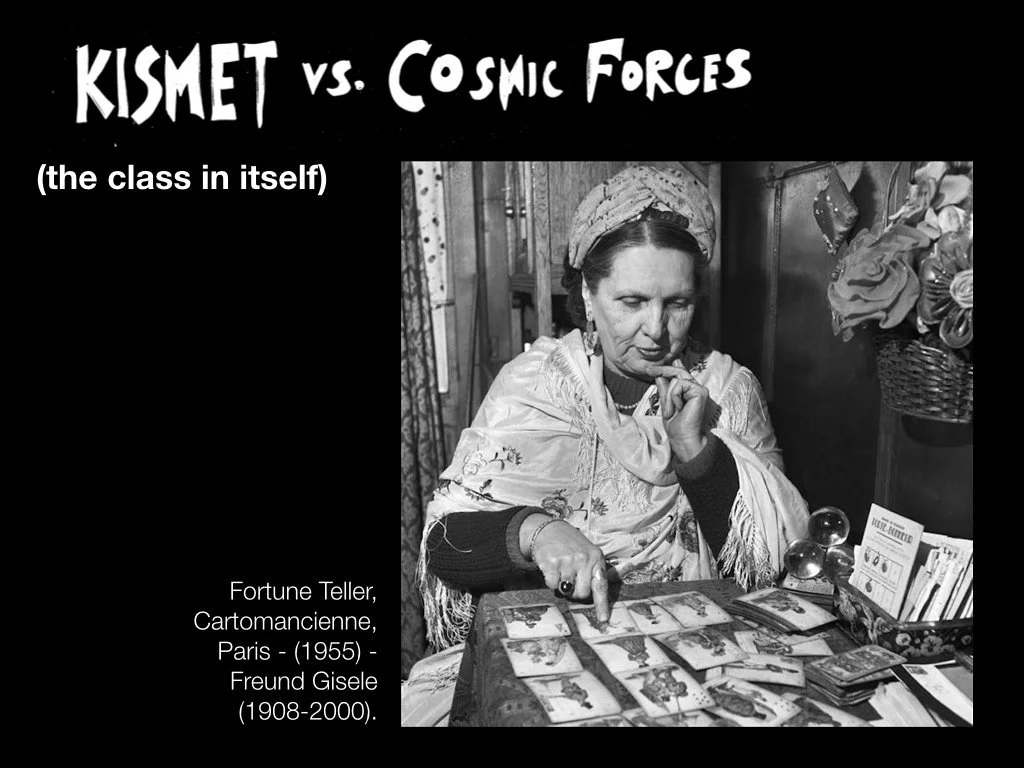

Earlier mythologies, like the “great” monotheistic faiths, are presented by Adorno as partial missteps on an overall path toward reason. [12] But newer myths represent a faltering of the telos. Mythology, for Adorno, is on a one-way street towards degeneration, reinforcing “commands of totalitarian structures” and morphing “thought” into “capitalist forms.” [13] While Adorno’s equation of authoritarianism with the occult may describe certain occult practices, other practices have a far greater sense of contingency and subjective interpretation (horoscopes vs. tarot cards for example). This variability is, in fact, how the experience of the exploited and oppressed subject meets occult irrealism. For the working-class subject even the smallest random event can have cosmic implications; a car breaking down can become a life changing event. In this context, certain kinds of esotericism become a negotiation with seemingly random fate. What makes this cultural negotiation critical, reactionary, or “common sense” in an irreal idiom, depends on its coding or expression.

The “spiritual,” in Adorno’s “Theses,” is marked by original sin, tied irrevocably to alienation, the commodity form, and its fetishism. [14] Spirit is, for Adorno, irrationally projected onto objects. But the projection of human characteristics on the inanimate objects (that are economically fused with the bodies of laborers) is not inherently reactionary. This cybernetic solidarity can also be an outgrowth of an empathetic impulse, related to the aforementioned negotiations with fate. Denied agency a worker may project agency onto their tools (see gestalt theory): “If my tools can be free, perhaps I can be free?” There are artists who anthropomorphize tools as a strategy to aesthetically valorize labor (see Anupam Roy and Adam Turl).

Adorno mocks such experience, arguing that occultism is “the complement of reification;” [15] as the world ceases to have meaning for the individual, and as rationality fails the subject, the subject recuperates meaning “by saying abracadabra.” [16] This begs the question, however — if “rationality” has failed the masses, is it “rational” to blame the masses for said failure? After all, it isn’t the masses who have failed “rationality” but vice-versa. For a contemporary “essential worker,” the “rationality” of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has failed. Would Adorno have us ridicule the death curses of grocery clerks, teachers, meatpackers, and nurses?

Indeed, the “Theses” necessitate condescension. Adorno argues, “[o]ccultism is the metaphysics of dunces.” [17] The mediums, he claims, offer very little to their patrons, “nothing more significant than the dead grandmother’s greetings.” [18] Because the subject has nothing, he argues, they are offered more of the same: “[W]orthless magic” lights up a “worthless existence,” (emphasis added). [19] Of course, a grandmother’s message is likely somewhat less banal to the persons who love her. Moreover, illuminating so-called “worthless lives” is central to any serious socialist or working-class art practice, precisely because there are no “worthless lives,” because the very notion of worthless lives is an adaptation and concession to the normative evaluations of capitalist ideology.

Adorno further argues that all esoteric epistemology as inherently anti-Semitic, that the connection between the occult and the anti-Semitic “is not only pathic,” but “lies in the fact that in the lesser panaceas, as in superimposed pictures, consciousness famished for truth imagines it is grasping a simply present knowledge denied by official progress in all its forms.” [20] It is self-evident that some occult traditions mirror or embrace anti-Semitism. But the trope of contested secret knowledge can also be read in an entirely different manner, in the manner of Karl Marx, Antonio Gramsci, and György Lukács, [21] the manner of ideology, hegemony, and class consciousness. The differences between left and right esotericism are in the subjective quality of this knowledge. In fact, if the knowledge of working-class consciousness was not at least partially hidden, capitalism could not continue to exist. How is this not “knowledge denied by official progress in all its forms”? [22]

Adorno argues that occultism contradicts rational progress, severing “body and soul” in a “kind of perennial vivisection.” [23] But this is nothing more than a reverse Cartesian trap. Dreams and visions are part of the material world. For Adorno, the “cardinal sin of occultism is the contamination of the mind and existence, the latter becoming itself an attribute of the mind.” [24] Occultism, for Adorno, is pure idealism, [25] an “ultimate exaltation of bourgeois consciousness.” [26] But the mind and existence cannot “contaminate” each other as they are both part and parcel of being. Adorno misunderstands the Marxist critique of idealism as bourgeois ideology and employs it as if it were an argument against all aspects of the mind -- which is itself part of the material. The mind can no more contaminate existence than a tree can contaminate a forest.

Kimset (The Class In Itself) vs. Cosmic Forces

What distinguishes critical irrealism from fascist occultism is largely their different orientations with and/or against larger forces, real or imagined, that constrain individual subjectivity. For example, Nazi occult policy and ideological discussion in the 1930s tended to support the “scientific occultism” of ariosophy and so-called cosmic occultism, while tending to be hostile, and to periodically repress, more popular commercial occult practices because these emphasized questions of individual fate (kismet), and exhibited international and cosmopolitan (read: Jewish) influence. [27] German fascism was suspicious of popular occultism, in part, because of its focus on individual fate. The commercial was suspect — and the “scientific” was often sponsored by the state. In other words, the Nazi approach to the subject tended to be one of ideological contestation. As Eric Kurlander observes, citing Corinna Treitel, the Nazi policy was different from the Wiemer policy on the occult, “not in epistemological but in ideological terms.” [28]

One of the major “anti-occultist” groups in Nazi Germany was the Ludendorff Circle — comprised of Field Marshall Erich and Mathilde Ludendorff, and Nazi Police commander Carl Pelz, among others. [29] Mathilde Ludendorff explains the political and cultural terrain of this esoteric conflict by placing popular occult practices (Tarot, etc.) in opposition to a “scientific” German belief in the “universal spirituality of the divine.” [30] According to Ludendorff, “scientific occultism” focuses on the cosmic and the national fate of the “German people,” (of course related to ariosophy and other racist ideas). [31] A pattern of cosmos vs. kismet was also born out in official policy, although not in those terms per se — focusing periodic repression on “occult groups that promoted ‘corrosive individualism and dangerous internationalism.’” [32] Commercial astrology was banned in 1938. [33]

A preoccupation with random individual fate in popular occultism mirrors the necessary pre-occupation of the non-capitalist subject with random fate in a precarious capitalism. As noted, the vagaries of everyday life for workers compel symbolic negotiation with this randomness. [34] This focus on individual subjectivity, while quite at home in “normal capitalism,” can run afoul of the repurposing of the individual toward the fascist collective and the individual’s semi-sexual subordination to the fascist leader-cult (see the hostility in the US far-right toward “snowflakes,” i.e. individuals). In “normal capitalism,” precarious individual fate is both phenomenological and an expression of liberal bourgeois ideology; the Horatio Alger myth, etc. In this way popular occultism, far from automatically being fascist, is often a representation/manifestation of the “class in itself” within the free market.

Of course, it is through the class struggle that the “class in itself” becomes conscious and organized; becomes a “class for itself.” As Marx argues in The Poverty of Philosophy:

Economic conditions had first transformed the mass of the people of the country into workers. The combination of capital has created for this mass a common situation, common interests. This mass is thus already a class as against capital, but not yet for itself. In the struggle, of which we have noted only a few phases, this mass becomes united, and constitutes itself as a class for itself. [36]

Popular occultism seeks to symbolically negotiate individual fate (kismet) with and against larger forces. Fascist occultism seeks to symbolically become one with those larger (cosmic) forces. As Locust Review writes, in response to the Jase Short essay on Covid 19, “Under an Alien Sky” [37]:

In one sense, our side reasserts the subjective by fully attacking the alien sky, and in so doing demonstrates that the alien sky is not truly alien. It is a product of social relations in interplay with the existential condition. The disparate threat has a source - normative racist capitalism. The enemy has a name. Capital is demystified. But in the process of this exposure the marvelousness of our lives is restored. Human beings return to the center of myth.

The fascist occultic chooses the opposite response. This is how the capitalist death cult works at the individual level. Subjective meaning, for the fascist, is regained by becoming one with the alien sky -- becoming one with normative racist capitalism. In fascism, capital becomes the center of myth. (Most) human beings become NPCs, mere trash to be cleared from the dungeon. [38]

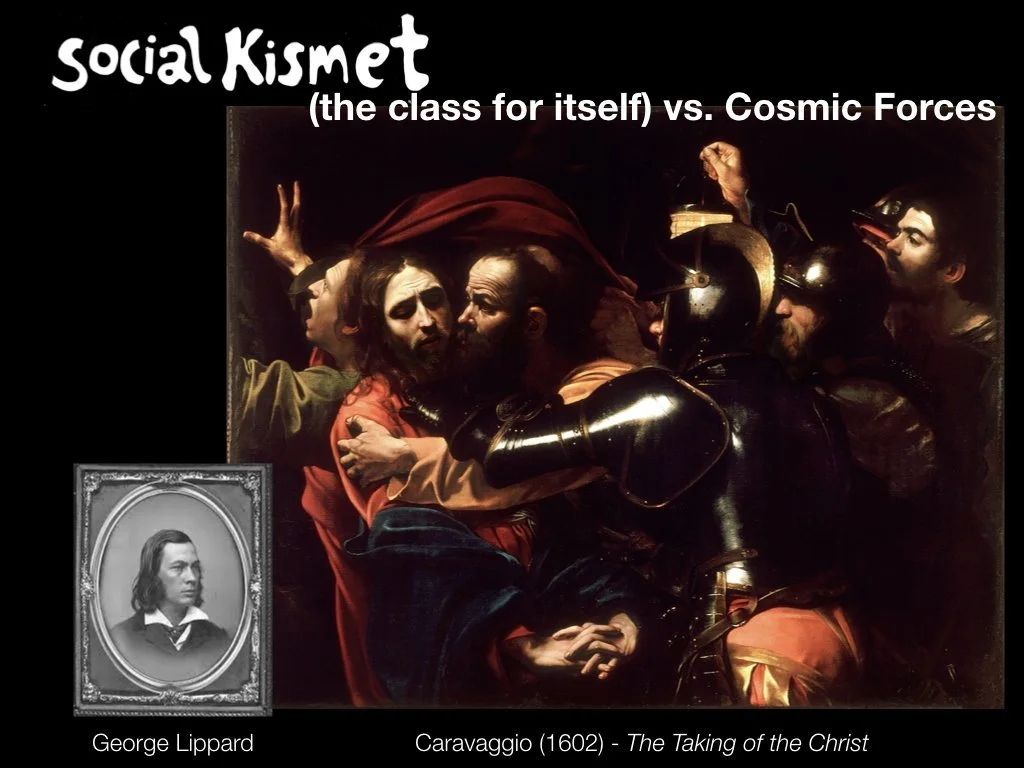

Social Kismet (The Class For Itself) vs. Cosmic Forces

ONLY THE class struggle itself can transform the class, en masse, into a self-conscious and self-organized movement. But this transformation can be approximated, described, examined, or shown in art, at both the molecular and mass level. Even during large shifts in class-consciousness, in which millions of workers move into action, as with the French May or the recent sectional struggles in India, collective class consciousness is also an individual experience. Each worker has, even during mass turmoil, a personal moment (or series of moments) on the road to Damascus. This molecular class consciousness arises with and against previous experiences. Class consciousness is both an individual/subjective as well as a class-wide event. It is an experience of becoming conscious of the external forces, the alien sky, the relations of capital, etc., that constrain one’s life, the necessity of destroying these constraints, and the necessity of combination with other constrained persons to assault said forces.

As Dan McKanan writes, the 19th century esoteric working-class fiction of George Lippard and Ignatius Donnelly deals with the “ambiguous agency” of working class characters; they have free will but are constrained by both capitalist and magical forces. [39] In the context of Lippard’s world-building, McKanan notes, a preferred individual fate, or kismet, can only be realized in relationship to social solidarity; which I refer to as social kismet. In Lippard’s novel, The Nazarene, Christ (as carpenter) becomes divine through a meditation on social class. [40]

Indeed, both Lippard and Donnelly built complex theologies [in their fiction] — by which I mean religious reflection in general, not exclusively reelection on the doctrine of God — on the foundation of their belief that Jesus of Nazareth had become a class-conscious worker with a revolutionary social blueprint. For them, this was the esoteric secret par excellence. [41]

Speculative world-building is implicitly tied, for critical irrealism, to ambiguous agency or constrained subjectivity. The working-class subject, whose life and imagination are constrained by capitalism, is compelled to imagine other worlds -- political, personal, speculative, mythological, scientific, magical -- against the existing world; against the prosaic realism that is, depending on race and other factors, killing us more slowly or more rapidly. The reductive “theory” that the narrative or symbolic evocation of supernatural, speculative, or otherwise mysterious forces is inherently reactionary is overturned by the very experience of working-class life. “[T]he existence of invisible, oppressive forces” [42] describes anti-Semitic conspiracy theory but it also the way in which most people experience secular abstractions like “the economy.”

In Lippard’s speculative fiction, in an appeal to esoteric and mystical forces (standing-in for social forces and the existential condition) a spiritual valorization of the individual (Jesus) is realized through an otherwise hidden class-consciousness, a social kismet, a collective-individual fate.

With and Against Suvin’s “Cognitive Estrangement”

WHILE ADORNO argues that the occult is inherently reactionary, Darko Suvin argues SF is inherently progressive. Borrowing from Bertolt Brecht’s concept of estrangement or alienation in the theater -- meant to provoke critical reflections through various distancing techniques -- Suvin describes SF as producing a kind of cognitive estrangement. [43] For Suvin, the scientific aspects of SF, read against an irrational capitalism, produce this effect. [44] But, as China Miéville argues, while Suvin is right about the estrangement potential of speculative fiction in general, he privileges science in such a way that is itself ideological. [45]

Although Suvin adapts Brecht’s concept of estrangement he makes several new assumptions and arguments, crystalized in his pairing of the word “cognitive” with estrangement, particularly in his emphasis on a narrative-scientific approach to a “strange newness,” or “novum.” [46] Suvin recognizes the importance of alterity itself -- that is, the importance of irrealist world-building itself — examining folk tales and the “voyage imaginaire,” arguing they “are a mirror to man just as the differing country is a mirror for his world,” and that this “mirror” is “a transforming one, virgin womb and alchemical dynamo: the mirror is a crucible.” [47] For Suvin, however, the key difference of the imagined alterity in SF, as compared to other irrealist speculations, is that the SF produces “a supposedly factual” and scientific alterity. [48]

Suvin argues, much like Adorno, that myths are reactionary as they “absolutize” and personify “apparently constant motifs from sluggish societies,” whereas “SF, which focuses on the variable and future-bearing elements for the empirical environment, is found predominantly in the great whirlpool periods of history…” [49] Fantasy stories — “ghost, horror, Gothic, weird” — impose “anti-cognitive laws into the empirical environment,” are reactionary and promote a “socio-pathological phenomenon.” [50] Miéville summarizes, “[a]s one of the various Others implied by that model [Suvin’s model of cognitive estrangement], generic fantasy comes in for a particular savaging, because, though it also ‘estranges,’ it is ‘committed to the imposition of anti-cognitive laws,’ is ‘a sub-literature of mystification,’ ‘proto-Fascist, anti-rationalist, anti-modern, ‘overt ideology plus Freudian erotic patterns.’” [51]

Miéville aims not to discard Suvin’s contribution but to salvage it from its positivistic bias. [52] As the “science” of SF is often incidental and not always particularly scientific, [53] parsing science from non-science in SF reduces “theory to the job of a mere border guard.” [54] SF estrangement, he argues, comes from “a function of (textual) charismatic authority.” [55] This moves SF estrangement squarely into ideological territory, and turns the ideological lens back on Suvin’s privileging of science itself. [56] As Miéville observes, Suvin gives us a “fantasy of a middlebrow-utopian bureaucracy,” [57] elevating the archetype of the “SF hero, the engineer,” and a “surrender of cognition to authority,” reflecting not an “abstract/ideal ‘science,’ but capitalist science’s bullshit about itself.” If the subject of Marxist theory is, first and foremost, the exploited and oppressed, the subject of Suvin’s theory is the engineer, the scientist, the expert.

It is therefore unsurprising that Suvin’s positivist bias minimizes the fact that capitalist ideology tends to present capitalism itself as rational; all the more so under the cultural logic of capitalist realism. Suvin and Adorno each ignore or minimize the way capitalist rationality and realism — including its science -- are experienced by the non-capitalist subject; as seemingly abstract forces that stifle both material and mental/imagined life; often as irrational examples of the rational. See, for example, the March 2021 CDC declaration, contradicting all previous declarations, that a mere three-feet social distancing is all that is required in public schools. [58] As Miéville observes, “the ‘rationalism’ that capitalism has traditionally had on offer is highly partial and ideological.” [59]

Brecht: Estrangement is About Subjectivity + Social Class Not “Science”

MIéVILLE SALVAGES the broader estrangement potential of SF and speculative fiction, repositioning it in ideological terms. This returns speculative estrangement to its Brechtian roots. While Brecht, the author of Galileo, often appeals to the importance of science in his essay, “A Short Organum for the Theatre,” he explicitly argues that his ”theatre for a scientific age was not not science but theatre,” and therefore its aesthetics had to be reckoned. [60] Brecht has long been misunderstood, often by bourgeois academics and artists, as someone mostly concerned with the exposure of cultural tropes, when he is interested in both their use and their exposure. Brechtian theater is not against the seduction of songs, comedy, and drama. Brecht wants the audience to emote and think critically. As he argues, “nothing needs less justification than pleasure.” [61]

For Brecht the promise of science is fettered by capitalism and class society. But science itself is contested, producing innovation as well as barbarisms like “the explosion at Hiroshima.” [62] Instead of critical theater aligning itself with an abstract “science,” Brecht calls for an alliance “with those who are necessarily most impatient to make great alterations:” an alliance of art and the proletarian. [63] Criticality and association with the working-class are co-dependent [64] and far more important than a particular textual attitude toward science.

Critical theater is, Brecht argues, both a game of “entertainment” and “wisdom.” [65] As theater interacts with audiences who are alienated by the experiences of capitalism, they must be alienated again to become critical because the structure of the theater itself “shows the structure of society (represented on stage) as incapable of being influenced by society (in the auditorium).” [66] Therefore, Brecht argues, we need theater that “encourages those thoughts and feelings which help transform” both life and theater (emphasis added). [67] This is what Brecht calls the “alienation effect,” also known as the estrangement effect: “[a] representation that alienates is one which allows us to recognize its subject,” he writes, “but at the same time makes it seem unfamiliar.” [68] Not only does this require both recognition and the unfamiliar, there is contingency to alienation/estrangement. [69] Brecht argues, “our representation must take second place to what is being represented, men’s life [sic], together in society; and the pleasure felt when the rules emerging from this life in society are treated as imperfect and provisional. In this way the theater leaves its spectators productively disposed even after the spectacle is over,” (emphasis added). [70]

Estrangement does not imply the removal of spectacle or seduction, it means the spectacle is constructed in such a way that allows for both the critical and emotive. Brechtian estrangement is about dialectical tensions — science and aesthetics, entertainment and wisdom, pleasure and criticality, thoughts and feelings, recognition and the unfamiliar — employed with an emphasis on subjective imperfection and provision. Brechtian estrangement is therefore an aesthetic and ideological operation, related most of all to proletarian interests and experience. Understanding this is a key part of understanding the contested nature of irrealism, and the estranging potential of critical irrealism. It is the world-building alterity of irrealism that allows for a possible estrangement effect; when a constructed or coded imaginary is read against “reality,” which is, generally speaking, capitalism’s narrative about itself (its ideology). What makes this coding critical or reactionary, or a mere reflection of bourgeois common sense, is most of all the ideological situation of the subject in relation to larger forces.

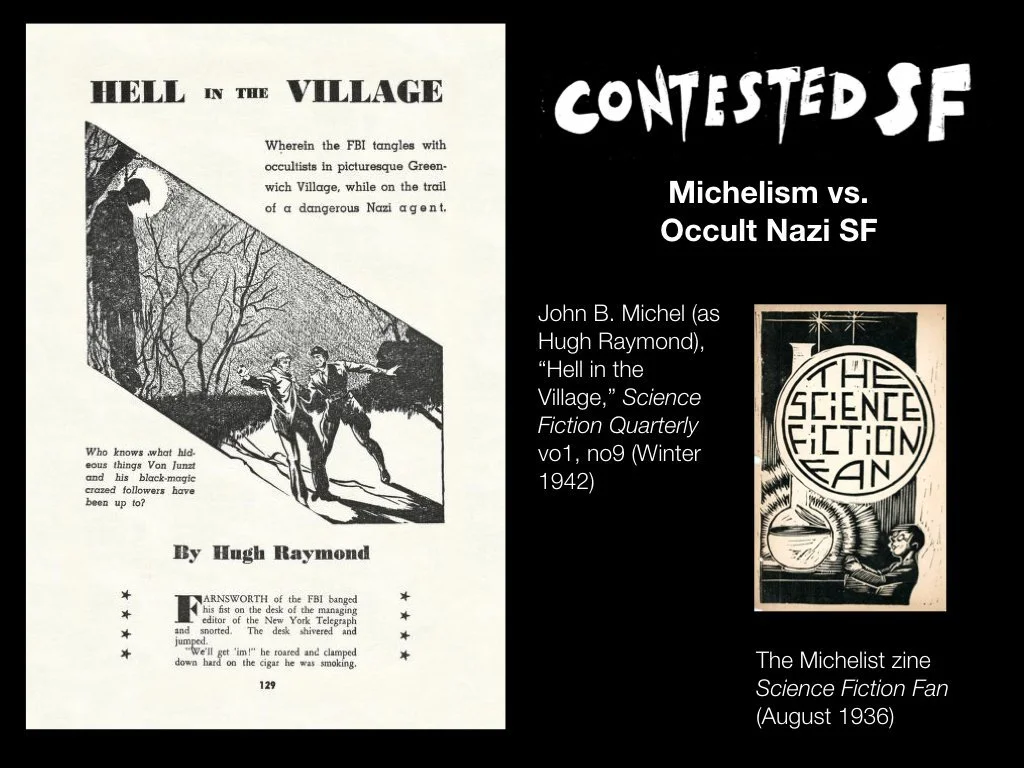

Contested SF: Taking Over SF for Communism

IN CONTRAST to Suvin’s assumption that SF is inherently progressive, SF, like the occult and esoteric, is politically contested. Moreover, even self-consciously communist SF writers and artists have had a contradictory relationship to positivist science, for example, Soviet SF authors influenced by the esotericism of Russian Cosmism, [71] and the Michelist/Futurian movement of SF authors in the United States in the 1930s-1940s. The Michelist attempt to politicize SF, while appealing to the scientific, was in many ways in opposition to a bourgeois ideology of science.

The Michelists were a group of young communists who eventually had a substantial role in shaping American SF during and after World War Two, beginning with their most militant activity during the Great Depression. [72] While zines are mostly associated with the 1970s and 1980s punk milieu, the earliest zines were tied to SF fandom, which, much like early punk, did not clearly demarcate artists and fans. [73] The Michelists were part of this zine fandom, a fandom that began with Hugo Gernsback’s 1926 publication of the first US SF magazine, Amazing Stories. [74] Sean Cashbaugh notes that Gernback’s approach to SF was a “celebration of American modernity” and “a celebration of American corporate and industrial success.” [75] The Great Depression wounded the Michelists’ scientific utopianism. [76] They started to call “apolitical” or pro-capitalist scientific utopianism the “Gernsback Delusion,” — a denial of how progress had been interrupted by capitalism. [77] Eventually the Michelists renamed themselves the Futurians and by the early 1940s their members played important roles in SF publishing.

In 1937, they gave a speech, written by John B. Michel and delivered by Donald Wollheim, at the “Third Eastern Science Fiction Convention in Philadelphia,” “Mutation or Death,” “denouncing SF publishing and its fandom, citing their mutual antipathy toward domestic economic depression and the rise of fascism abroad…,” arguing “if SF did not change — or in fan slang, ‘mutate,’ — the genre faced certain death.” [78] The “‘fantastic situations’ of SF” became a kind of rhetoric [79] that the Michelists could use against capitalist reality: The subject “‘shorn of his bonds,’ and free from the ‘wars, the sickness of body and spirit, the incredibly petty economics, the grinding monotony of work and sleep, of birth and death with naught between but drudgery.’” [80] In “Mutation or Death” Michel writes, “how sick we are at base of this dull, unsatisfying world, this stupid asininely organized system of ours which demands that a man brutalize and cynicize himself for the possession of a few dollars in a savage, barbarous, and utterly boring struggle to exist.” [81]

John Michel’s 1942 short story, “Hell in the Village,” published in Science Fiction Quarterly [82] can be read as an anti-positivist parable; as well as an anti-fascist polemic against the Gernsback Delusion. A reporter, a professor, and an FBI agent (named Farnsworth of all things) are trying to find a Nazi saboteur that mysteriously evades capture. Unable to apprehend this spy they resort to consulting a group of occultists in Greenwich Village. With the help of the occultists they contact the spirit world — which turns out to be an anarchist commune — and discover the Nazi spy has been using the spirit realm to evade capture. In an act of ethereal solidarity the spirits expel the fascist and hand him over. [83] In the 1942 novelette, “The Inheritors,” published in Future magazine, written by Michel and Robert Lowndes, the characters are literally constrained by the environment. [84] On an Earth where periodic oceans of toxic foam appear that one must wade through to move from place to place, the entire human race lives inside giant industrial compounds exchanging missiles with each other. The people who live in these industrial fortresses are driven generationally mad by the noise and pollution. [85]

The dialectic of subject and social totality is repeated in the post-war Judith Merril short story, “That Only a Mother,” published in Astounding Science Fiction. The story follows a pregnant woman named Margaret who works for a government agency. Her husband is abroad with the military. Merril depicts a constant noise of rumor about mutated newborns, mutations possibly caused, it is not clear, by ongoing atomic tests and war. Margaret communicates with her husband by telegram, and after giving birth, she notes how talented their daughter is: At six months old she can already talk! When her husband finally returns he realizes their child is one of these mutants, a genius worm with a human head. [86] Merril makes no moral judgment -- regarding either the mother or the father, or the mutant child. This is left open; raising questions about social reproduction, war, the environment, their mutual interaction, and the relationship of these characters to these forces. Moreover, given the historic Michelist use of the word “mutation” as a necessary response to the stagnation of SF and capitalism itself, and given Merril’s Trotskyism, it begs the question about how sinister the daughter’s mutation actually is.

In another example of how the Michelist practice contradicts Suvin’s positivist bias as well as the Gernsback Delusion, Donald Wollheim’s 1942 short (almost flash) fiction, “Bomb” is more surrealist than SF. Astronomers observe a protuberance growing from the moon. Over time it becomes clear that the moon is turning, more or less, into a giant cartoon bomb. A fiery comet rapidly approaches its wick. [87] This almost surrealist attitude was repeated in a number of Michelist projects, including the games that they designed in their collective housing and the more absurd pieces placed in their self-published zines. [88]

As with fascist SF there is slippage on the “scientific.” Whereas fascist SF tends to reduce personality to “cosmic” forces, the slippage in left irrealism tends to prejudice individual and social imagination — in part through individual world-building. The Michelists/Futurians, Cashbaugh notes, dealt with “spheres of cultural production, those frequently cast as marginal or ephemeral, but nevertheless fill the everyday lives of individuals seeking radical alternatives.” [89] The scientific slippage is also about the nature of science itself. Lowndes argues: “socialism is science-fiction.” [90] For the Michelists, Marxism may be a theory of social science but it also becomes, equally, a fiction, a story, a narrative, a human mythology of emancipation. When they write, “stories dealing with the future and with science must by their very nature reflect upon man and man’s reactions,” [91] they are getting at questions of Brechtian estrangement and critical distance — as Cashbaugh implies [92] — prefiguring Miéville’s salvaging of Suvin’s core insight from positivist error.

Contested SF: Cycles of Fascism

Michelism, however, is just one part of SF history. At the very same time as the Michelists were agitating in American SF, Nazi mythology was being incorporated wholesale into German SF. [93] At the core of Nazi SF mythology was the subordination of the individual rather than the individual’s liberation. As Manfred Nagl writes:

In National-Socialism the contradictions and irrationalities of a classical capitalist socioeconomic system and its power structures were transmuted into an apparently ‘natural’ ideology and apology. The exploitative and class-bound power became racism, with a master-race and its leadership mystique; cycles of economic crisis and other-directedness became the cosmic law of recurrent cycles; the alienating character of science and technology misused as a means for ruling became central concepts of pseudo-religious secret cults…” [producing] “an obscure mixture of industrialism run wild with a ‘Blood and Soil’ theory.’” [94]

The German equivalents to American SF pulp magazines swelled with this Nazi mythology. [95]

For the Michelists, the larger forces depicted in speculative fiction were about the constraint on social equality and individual liberty. Understanding or escaping from this constraint required some kind of social consciousness or solidarity. For the fascist the solution to this problem is found, as Nagl observes, in becoming one with those larger forces; “the contradictions and irrationalities of a classical capitalist socioeconomic system and its power structures were transmuted into an apparently ‘natural’ ideology and apology,” (emphases added). [96]

The imaginary cosmology that flowed from this dynamic demanded a fig leaf of “science” and myth, and found it in concepts like Theozoology, first articulated by the defrocked monk, Adolf Josef Lanz. [97] Theozoology, or “racial metaphysics,” turned both science and mythology upside down: “[T]he simultaneous rejection of Darwinism and the acceptance of the pseudo-Darwinist ‘survival of the fittest’” [98] provided some of the base ingredients of Nazi SF, such as the “sado-masochistic desire for submission to an irresistible external force” and “the projection of one’s own destructive and primitive drives onto unpopular minorities.” [99] Theozoology, along with a broader “confused mass of abstruse concepts” were appropriated: “‘Glacial Cosmology,’ the Atlantis/Thule myth, Theozoology, and the Hollow World theory.” [100]

Key here is the concept of “glacial cosmology.” “The cyclic recurrence,” Nagl writes, “of Glacial Cosmogony ensured that Atlantis would rise again,” and provided a convenient explanation for the periodic displacement of “superior” Aryan rule. [101] This is a core trope of Nazi myth, repeated today in the Kekistan memes of the alt right: An idyllic Aryan-type society is disrupted by cosmic events, making their women available to inferior races. In order to recapture said women and restore order all will must be subordinated to a great leader. [102] Repeat.

Racial essentialism and cyclical cosmology appear in non-consciously fascist SF as well, as Aaron Santesso notes of the 1939 pulp (American) SF John Murray Reynolds story, “The Golden Amazons of Venus” published in Planet Stories. [103] Even largely “progressive” instances of popular SF like Star Trek reproduce speculative racial essentialism. This further undermines the Suvinian argument that SF is inherently progressive, as the disgraced “science” of eugenics has echoed throughout the genre for more than a century, whether explicitly fascist or not.

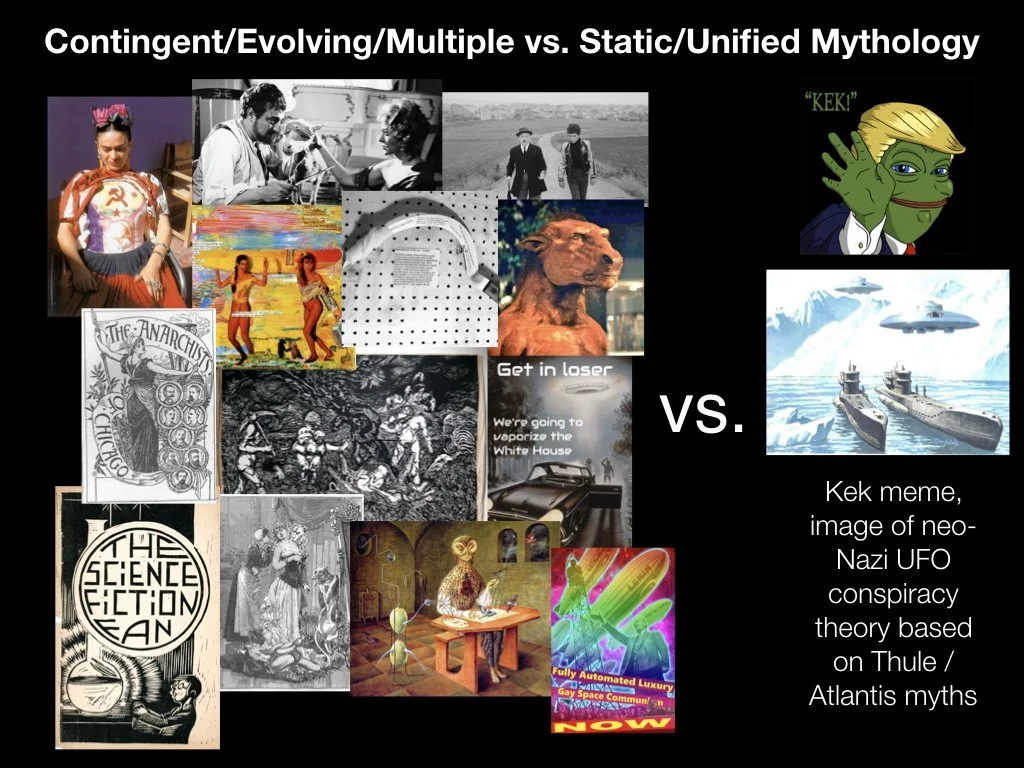

Contingent/Evolving/Multiple vs. Static/Cyclical Mythologies

THE SUBJECT within capitalism is constrained. Capitalism offers the random possibility of salvation by ascension and separation from the working-class. It offers gambling in a rigged casino. This is kismet; the class in itself. The socialist response is social kismet: liberation of the individual through the realization of social solidarity, the class for itself. The fascist response is to become the agent of constraint; signing up with variations of the capitalist death cult. [104] Because critical irrealism responds to the constraint of the individual with social kismet (an association of individual liberation with collective liberation) while fascist occultism seeks to subordinate the individual to a re-mythologized capitalism, we can see that critical irrealism exhibits a constantly evolving and contingent mythology, whereas fascist occultism tends to employ a fairly static set of myths — often a cyclical cosmology — that evolves in a mostly superficial manner.

As noted, Nazi tropes were reprised in the Cult of Kek memes that proliferated online in the aftermath of the 2016 US election. In this crowdsourced fascism, constructed on the chans in a semi-satirical idiom conditioned by Poe’s Law, an ancient kingdom called Kekistan was overwhelmed by Normistan and Cuckistan (the inferior races and their accomplices); and Kekistan must be restored. The flag of Kekistan — a green and black banner — is based on a Nazi battle flag. [105] The banality of this evil is almost palpable. [106]

Conversely, the evolving and contingent mythology of critical irrealism is represented in several traditions that can be called irrealist, as with early Soviet commissar of Enlightenment, A.V. Lunacharsky’s concept of god-building: a sort of free democratic construction of the spiritual, that is, like the class struggle itself, a process of becoming. [107] As Roland Boer reports, Lunacharksy’s nearly lost Religion and Socialism — lost due to disagreements before 1917 and the rise of Stalinism in the 1920s — outlines both this democratic evolutionary conception of the spiritual and the historically contested nature of religion itself. [108]

Critical irrealism’s contingent and evolving approach to mythology can also be seen in the arguments of the Surrealists — too often ignored by Marxist cultural criticism. Surrealism, with its advocacy of a variable and evolving mythology, or “myth in perpetual motion” as Michael Löwy writes, is “always incomplete and always open to the creation of new mythological figures and images.” [109] As the 20th century Afrosurrealists, Aimé Césaire and Juan Breá, note, this open and evolving mythology is connected to a core democratic conceptualization of mythology:

To make a world emerge where the exotic inhumanity of a junk shop was displayed; where we were only drawing forth the vision of grotesque puppets, gathering a new way to suffer, die, come resigned in a word to bear a certain human load? (Aimé Césaire) [110]

In the final analysis, the concept of quality is nothing but thedivination of human behavior at the expense of the broad dehumanization ofother behaviors. (Juan Breá) [111]

Critical irrealist world-building, like Lunacharsky’s god-building and surrealist mythologizing, is contingent on the material reality of the subject, and the subject’s personal construction of a counter-mythology. Far from contradicting classical Marxism, this approach to culture represents the unity of the philosophic-human Marx and the economic-partisan Marx. For Comrade Marx, the universality of the individual as a “free being” comes from our evolution as a biologically distinct social species. [112] This subjective value, however, is not some abstraction. It is woven into “the ensemble of the social relations.” [113] Therefore, to rephrase André Masson, critical irrealism is the “collective experience of individualism;” the aesthetic rapprochement of individual universality and the social ensemble. [114]

Each subject builds a world. All worlds are worthy.

QAnon

QANON, AFTER the January 6th putsch and the November election of President Biden, is in a process of regroupment. Prior to these events, QAnon operated as a sort of clearinghouse of right-wing conspiracy theories that functioned for its growing adherents like a real world ARG. It was a puzzle to be solved. But the core of the QAnon mythology was the idea that an international elite was kidnapping thousands of children in an effort to become immortal (or for sexual purposes) and that this would be thwarted by President Donald Trump in a cataclysmic event called “The Storm.” There are, as noted, a number of right wing, heterosexist, anti-Semitic, and fascist myths at work here. Chief among them are replacement theory, medieval blood libel, the leader cult, and an Americanized version of glacial cosmology (“The Storm.”) [116] QAnon mythology is, in the most literal sense, irreal. But this is not what defines its politics. Fascist irrealism does not critically estrange. It reclaims the subject in a re-mythologized -- but still utilitarian -- relationship to capital. Moreover, the participatory structure of QAnon is that of a “rationalist” game, as outlined by Holly Lewis. [117] There was no unique subjectivity to express beyond unearthing the hysterical conspiracies coded in the latest Q-Drop. [118]

The Irrealist Worker Survey: Queer Hearths of Limbo

LET’S COMPARE this to the variable mythologies created by the anarchist, socialist, and working-class readers of LR in the 2019/2020 “Irrealist Worker Survey;” in particular Beatrix Morel’s response to the question, “Do you dream of the end of the world?” [119]

Most souls automatically find themselves in heaven, which turns out to be a multidimensional holy battery created to boost god’s power. Only those who specifically made pacts with demons end up in hell, which isn’t so much a place of punishment as it is just some other god’s soul battery. The Queers build cozy enclaves with warm heaths in the perpetual rain of limbo. [120]

Here again we find a dynamic of social kismet, in a highly subjective individual mythology. Parasitical power is associated with the binary of heaven and hell; opposed to the human solidarity demonstrated in a queer limbo. If we compare Beatrix Morel’s passage with the core mythology of QAnon, the difference is not rationality in some crude positivistic sense. The difference is the relationship of the subject to “cosmic” forces (which are an irrealist stand-in for the material and ideological forces that shape and constrain our lives).

Mutation or Death

THE CONTESTED nature of irrealism is similar to Michael Löwy’s extensive outlining of the contested nature of Romanticism. In response to the Thermidor of the French Revolution, and the “rational” havoc wrought on the masses by industrialization, a number of artists and thinkers rebelled against capitalist utilitarianism. This produced both a left and right Romanticism. [121] Similarly, we have the failures of capitalist realism — in no less catastrophic form — economic crises, the plague, racist and heterosexist violence, imperialism, and climate disaster. This produces an irrealist cultural rebellion. But today’s fascists, unlike the déclassé right Romantics, are the direct agents of the forces that animate them. Fascist occultism does not really dream of a return to the pre-capitalist order, but dreams of personifying the capitalist death cult itself; as we saw in the “re-open the economy” protests in 2020.

Fascist occultism is static, prosaic, and, beyond its symbolic sadomasochism, mostly dull. It dresses up in new clothes but this is always superficial. It may claim (or seem) to oppose the rationality and realism of the capitalist center but it represents, in concealed form, the ultimate enforcement of capitalism’s vulgar utilitarian rationality. Our myth, by contrast, is rooted in a social understanding of individual fate, resolutely opposed to submission. Our myth is not one myth — it is millions of myths — in a contingent and evolving, democratic and anarchic construction; a process of becoming.

Adam Turl an artist and writer from southern Illinois — by way of Wisconsin, St. Louis, Chicago, upstate New York and Las Vegas. They are an artist and editor at Locust Review, a quarterly irrealist journal of art and literature, and a member of the Locust Arts and Letters Collective (LALC). They have had solo exhibitions at the Brett Wesley Gallery (Las Vegas), the Cube (Las Vegas), Project 1612 (Peoria, Illinois), and Artspace 304 (Carbondale, Illinois); and group exhibitions at Core Contemporary (Las Vegas) and Gallery 210 (St. Louis). In 2016 Turl was awarded a fellowship and residency at the Cité internationale des arts in Paris, France. They received their MFA from Washington University in St. Louis at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, and a BFA from SIUC. Turl is working on an evolving conceptual and visual art project, Born Again Labor Museum, with their partner Tish Turl, a writer and fellow LALC member.

Endnotes

Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (London: Zero Books, 2009).

See the first four Locust Review editorials, available at locustreview.com, and the Locust Arts and Letters Collective (LALC) essay in Red Wedge Magazine: LALC, “Socialist Irrealism vs. Capitalist Realism,” Red Wedge Magazine (February 18, 2020): http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/socialist-irrealism-vs-capitalist-realism ; “We Demand an End to Capitalist Realism,” Locust 1 (Fall 2019), 2; “Workers! Jump the Shark,” Locust 2 (Spring 2020), 2; “Labor Under an Alien Sky,” Locust 3 (Summer 2020), insert; “Norming in America,” Locust 4 (Winter 2021), insert.

Michael Löwy, “The Current of Critical Irrealism: ‘A Moonlit Enchanted Night,’” in Matthew Beaumont, ed. Adventures in Realism (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 193

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto, (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005), 47

See Adam and Tish Turl, “What is BALM?,” Locust Review 1 (Fall 2019), 20

LALC

As this summarizes a vast evolving collaborative literature I am not citing specific sources. Instead I would direct readers to the “Marxists on Fascism” page of marxists.org, featuring an index of works by aforementioned authors and others: https://www.marxists.org/subject/fascism/index.htm

For a more developed sketch of this understanding of fascism see Adam Turl, “The Urgency of Anti-Fascism,” Tempest (October 1, 2020): https://www.tempestmag.org/2020/10/the-urgency-of-anti-fascism/

Theodor Adorno, “Theses Against Occultism,” in The Stars Down to Earth and Other Essays on the Irrational in Culture (London: Routledge, 2002), 172

See Julian Strube, “Doesn’t Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism?” in Hanegraff, Forshow, and Pasi, eds, Hermes Explains: Thirty Questions About Western Esotericism. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 225-231

Of course the narrative of a thwarted teleological progress is itself problematic in relationship to the history of colonization and imperialism; but it also problematic in the “internal” history of Europe itself, and to the subjectivity of all exploited and oppressed persons.

Adorno, 172

Adorno, 173

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

Adorno, 175

Adorno, 176

Adorno, 176

Adorno, 175

See Karl Marx, The German Ideology (1845), available at the Marxist Internet Archive: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/ , Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (New York: International Publishers, 1992), available online: https://ia800503.us.archive.org/17/items/AntonioGramsciSelectionsFromThePrisonNotebooks/Antonio-Gramsci-Selections-from-the-Prison-Notebooks.pdf and György Lukács, History and Class Consciousness (Boston: MIT Press: 1972).

Adorno, 175

Adorno, 177

Adorno, 178

Ibid

Adorno, 179

Eric Kurlander, “The Third Reich’s War On the Occult: Anti-Occultism, Hitler’s Magicians’ Controversy, and the Hess Action,” in Hitler’s Monsters (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2017), 99 - 130

Kurlander, 101

Kurlander, 106

Kurlander, 106-107

Kurlander, 103

Kurlander, 109

Kurlander, 109

For a good discussion of this dynamic see Locust Radio, Episode 4, “Make Acid Communist Again,” (December 21, 2020), hosted by Adam Turl, Alexander Billet, and Tish Turl, produced by Drew Franzblau, with guests Omnia Sol and Adam Ray Adkins: https://www.locustreview.com/locust-radio/make-acid-communist-again

See the classic Susan Sontag essay, “Fascinating Fascism,” in Susan Sontag, Under the Sign of Saturn (New York; Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1993), 73-108. The first half of the essay in particular deals with the dynamics of death as they relate to fascist aesthetics.

Karl Marx. The Poverty of Philosophy, Chapter 2: “The Metaphysics of Political Economy - Strikes and Combinations of Workers,” retrieved on March 15, 2021: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/ch02e.htm

Jase Short, “Under an Alien Sky,” Red Wedge Magazine (April 9, 2020): http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/under-an-alien-sky

Editorial. “Labor Under an Alien Sky,” Locust Review #3, (Fall 2020), insert page 4

Dan McKanan, “George Lippard, Ignatius Donnelly, and the Esoteric Theology of American Labor,” In C.D. Cantwell, H.W. Carter, and J. G. Drake, The Pew and the Picket Line: Christianity and the American Working Class. (Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 35

McKanan, 37

McKanan, 24

McKanan, 41

Darko Suvin. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre (Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2016), 15

Suvin, 16-17

China Miéville, “Cognition As Ideology: A Dialectic of SF Theory.” In Miéville and Bould, eds, Red Planets: Marxism and Science Fiction (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2009), 240

Ibid.

Suvin, 17

Suvin, 18

Suvin, 20

Suvin, 21

Miéville, 231

Miéville, 232

Miéville, 233

Miéville, 237

Miéville, 237-238

Miéville, 240

Miéville, 240

Amy Kamenetz, Cory Turner, Allison Aubrey, “CDC Says Schools Can Now Space Students 3 Feet Apart Rather Than 6” National Public Radio (March 19, 2021), available online (accessed on April 5, 2021): https://www.npr.org/2021/03/19/978608714/cdc-says-schools-can--space-students-3-feet-apart-rather-than-6

Miéville, 241

Bertolt Brecht, “A Short Organum for the Theatre,”. In Willet, J., ed, Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1992), 189-205, 179

Brecht, 180

Brecht, 184

Brecht, 186

Ibid

Ibid

Brecht, 187-189

Brecht, 190

Brecht, 192

Brecht, 194-195

Brecht, 205

See George Young, The Russian Cosmists: The Esoteric Futurism of Nikolai Fedorov and His Followers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), and Bernice Rosenthal, The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997)

Sean Cashbaugh, “A Paradoxical, Discrepant, and Mutant Marxism: Imagining a Radical Science Fiction in the American Popular Front,” Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 1(10). (Spring 2016), 63-106

Cashbaugh

Cashbaugh, 67

Ibid.

Cashbaugh, 63-67

Cashbaugh, 71-73

Cashbaugh, 63

Cashbaugh, 74

Cashbaugh, 75-76

John B. Michel, “Mutation or Death,” (1937) available online here: https://fanac.org/fanzines/Sense_of_FAPA/Mutation_or_Death.html

John B. Michel, as Hugh Raymond, “Hell in the Village,” Science Fiction Quarterly, (1)9 (1942), 129-137

Michel

John B. Michel and Robert Lowndes, “The Inheritors,” Future (3)1 (1942), 54-69

Michel and Lowndes

Judith Merril, “That Only a Mother,” Astounding Science Fiction (41)1 (1948), 88-95

Donald A. Wolheim, “Bomb,” Science Fiction Quarterly (1)9 (1942), 81

See Damon Knight, The Futurians (Golden, CO: ReAnimus Press, 2015), 35-41

Cashbaugh, 93

Cashbaugh, 74

Cited in Cashbaugh, 74

Cashbaugh, 74

Manfred Nagl, “SF, Occult Sciences, and Nazi Myths.” Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 1. No. 3 (Spring 1974), 185-197

Nagl, 185

Nagl, 186

Nagl, 185

Nagl, 185

Nagl, 187

Nagl, 187

Nagl, 188

Nagl, 188

Nagl

Aaron Santesso, “Fascism and Science Fiction,” Science Fiction Studies (41)1, (2014) 136

See Sontag, see also Peter Frase, “The Rise of the Party of Death,” Jacobin (March 24, 2020): https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/coronavirus-economy-public-health-exterminism and Salvage Editorial Collective, “The Tragedy of the Worker: Toward the Proletarocene,” Salvage (January 31, 2020): https://salvage.zone/editorials/the-tragedy-of-the-worker-towards-the-proletarocene/

David Neiwart, “What the Kek: Explaining the Alt-Right Deity Behind Their Meme Magic,” Southern Poverty Law Center (May 9, 2017): https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2017/05/08/what-kek-explaining-alt-right-deity-behind-their-meme-magic

Apologies to Hannah Arendt. See Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report of the Banality of Evil (New York: Penguin, 2006)

See Roland Boer, “Religion and Socialism: AV Lunacharsky and the God-Builders,” Political Theology (15)1 (March 2014), 188-209

Boer, 189, 203

Löwy, Morning Star: Surrealism, Marxism, Anarchism Situationism, Utopia (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2009), 18

Aimé Césaire cited in Franklin Rosemont and Robin D.G. Kelley, Black, Brown and Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2009), 75-76

Juan Breá cited in Rosemont and Kelley, 57

Karl Marx, “Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844,” in Robert Tucker, ed, The Marx-Engels Reader (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978), 75 - 76

Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach,” in Robert Trucker, ed, The Mark-Engels Reader (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978), 144-145

cited in Rosemont and Kelley, 2

I am interested here in the cultural coding of the QAnon phenomenon. I am not interested in covering here its detective story aspects. For example, the question, “Who is Q?” These questions have been covered extensively. See, for example, Cullen Holbeck, Q: Into the Storm, Episodes 1-6, HBO, March 21-April 4

Adriene LaFrance, “The Prophecies of Q: American Conspiracy Theories Are Entering a Dangerous New Phase,” The Atlantic (June 2020), accessed online on April 1, 2020: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/06/qanon-nothing-can-stop-what-is-coming/610567/

Holly Lewis, “How Collective Dreams Can End the Sleep of Reason,” paper presented at Historical Materialism 2020 conference, on the Locust Review panel, “Critical Irrealism as Socialist Cultural Strategy,” available here (November 2020): https://www.locustreview.com/editorial/event-irrealism-as-socialist-cultural-strategy-thursday-nov-12

I have not otherwise cited this section on QAnon as the rough contours of this widespread conspiracy are, at this point, common knowledge.

BALM, “Irrealist Worker Survey,” Locust Review 2 (Spring 2020), 21

Ibid

See Michael Löwy and Robert Sayre, Romanticism Against the Tide of Modernity (Durham; Duke University Press, 2002)

Subscribe to Locust Review for as little as $1 a month.

Submit work to Locust Review by e-mailing us at locust.review@gmail.com.