This article originally appeared in the print edition of Locust Review 11. Cover by Laura Fair-Schulz.

Colonizers write about flowers.

I tell you about children throwing rocks at Israeli tanks

seconds before becoming daisies.

I want to be like those poets who care about the moon.

Palestinians don’t see the moon from jail cells and prisons.

It’s so beautiful, the moon.

They’re so beautiful, the flowers.

I pick flowers for my dead father when I’m sad.

He watches Al Jazeera all day.

I wish Jessica would stop texting me

Happy Ramadan.

I know I’m American because when I walk into a room something dies.

Metaphors about death are for poets who think ghosts care about sound.

When I die, I promise to haunt you forever.

One day, I’ll write about the flowers like we own them.

- Noor Hindi, “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying” (2020)

OF COURSE, poetry is a craft. The above poem by the Palestinian-American poet Noor Hindi, circulated widely on social media, is a salvo against a particular kind of formalism that seems empty in the face of barbarisms like the genocide now being conducted by Israel’s colonial settler-state.

Poetry is a craft. But it isn’t just a craft. It is language. It is social knowledge. It is contested. It is self-expression. It evolves.

As fellow craft persons we have a tradition of helping each other master that craft. The arts are one of the few places where competition is, at least partly and however imperfectly, short-circuited by mutual attempts to help one another. That involves workshops and critiques.

It is important, of course, that we try to distance the criticism of work from criticism of the person (both when dispensing and receiving said criticism).

It is also important that we square the circle of inviolable self-expression and collegial respect.

At the same time, we have to ask: what is the social, political, conceptual and aesthetic content of a critique? What is the method of our workshops? What is the purpose?

What is a “well-crafted” poem?

The following is meant as a contribution to help us further unpack these questions.

Is there such a thing as an objectively “good poem”? How can that be quantified or qualified? What is the criteria for a “good” or “bad” poem?

The nature of poetry has been contested — and has evolved — over time. What constitutes a poem has shifted historically and geographically.

That doesn’t necessarily mean there is not a commonality or logic to what has been called poetry — and its relationship to imagery, musicality, pathos, and so on. But it does mean the way those things have been approached have varied significantly.

This is even more the case for poetry after modernism; after futurism, after free-verse, after conceptual poetry. What is poetry now? Can it be giant letters on a page, in between more traditional forms, and fusions of verse and prose — see, for example, Richard Hamilton’s Discordant.

Does poetry need to be clean? Is it sometimes good if the poems aren’t clean?

What is clean?

For example, what is being “taken out of the poem?” This is a common complaint in many workshops. For Bertolt Brecht, being “taken out” of a poem or play was a strategy towards the reader or audience thinking critically. Lotte Lenya would sing “Jenny the Pirate” to an enraptured audience and then Brecht would walk on stage — to the annoyance of his collaborator Kurt Weill — and start reading from The Communist Manifesto.

Does our poetry need to imitate other poets and poems? Which poets? Should we imitate the forms and approaches of Shakespeare, Ai, Sylvia Plath, Brecht, Audre Lorde, William Blake, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Aimé Césaire, Amiri Baraka, Judy Jordan, Pablo Neruda, Mahmoud Darwish, Ahmad Shamlou, Emily Dickenson, André Breton, Walt Whitman, Federico García Lorca, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Allison Joseph, Rodney Jones, Richard Hamilton, Mike Linaweaver, Leslie Lea?

Which ones? Do (or did) those poets all agree on what poetry should look like? Does our poetry take something from one poet and something else from another? Doesn’t poetry — in form and function — sometimes (or often) argue with itself as a discipline about what poetry should be?

To what extent are our poetic gestures conceptual, visual, formal, musical?

If we assume a priori there is such a thing as an objectively “good poem” — but do not unpack what that means — do we not risk making normative evaluations of other poets’ work?

In other words, do we sometimes base our critiques on unexamined assumptions about what poetry is or should be? Where might those assumptions come from? What are their ideological origins?

What if a poem is “technically good” (well written, good images, beautiful sounds) but its subject matter is facile? What if we don’t agree about the subject matter? Is it a “good poem?”

Is a good poem that is politically reactionary a good poem? Is a bad poem that expresses the righteous anger of the oppressed a bad poem?

Is the goal of workshop to help our fellow poets realize what they are trying to do — help them improve their own projects — or is it to remake their work along the lines of our own?

What is the goal of our own work?

What are our criteria?

What is the point of poetry? Is it that it has no point (in the common sense of the phrase)? If so, how do we evaluate something outside of utilitarian measurements?

Is the poem of a president the same as a poem of a prison inmate?

Is the poem of an owl the same as the poem of a field mouse?

Is the poem of a banker the same as the poem of a construction worker?

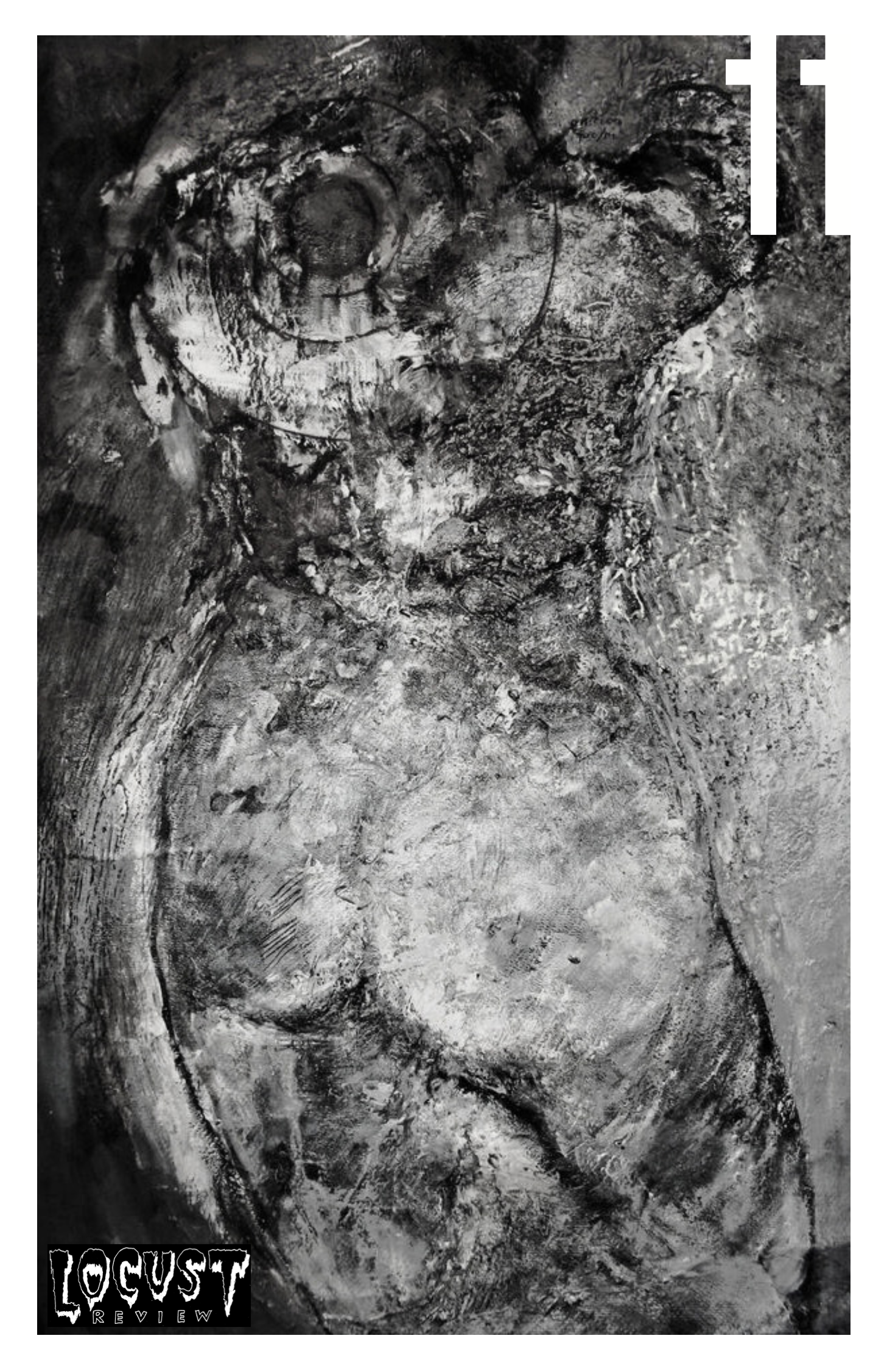

Tish Turl and Adam Turl, Katrina, mixed-media collage and painting on thrift store painting with cotton and ash (2024).

Subscribe to Locust Review for as little as $1 a month.

Submit work to Locust Review by e-mailing us at locust.review@gmail.com.