WE COME from the future. Or the past. It is hard to tell as both are being erased…

The time for sending messages in bottles has passed. As seas toxify and rise over the shorelines, who will be left to read them? Nonetheless, we have to communicate. So we communicate. To anyone who will listen. Through the haze of wine, cannabis, SSRIs, exhaustion, overwork, climate depression, and an overwhelming anxiety at the rise of new fascisms, we communicate. Because we must. Because, for the time being at least, we are human.

Hence what you hold in your hand. The first issue of Locust Review. A hidden transcript hidden even to ourselves; a riddle whose answer is another riddle; a song heard through static; a codex whose authors lost its original meaning even as they scribble furiously to rediscover it.

We’ve made this because we are sick. As you are. And we wish we could be healthy. But like all of you we’ve spent the past several years rifling through the images of billionaire fail-sons towering over crowds baying for the blood of black, brown, poor, and queer people. How do we stomach it? Particularly when we know that we have barely a decade until the atmosphere begins to shudder?

We don’t believe that a publication of arts and letters is a solution to any of this. No matter how steadfastly revolutionary it proclaims itself to be. But we do believe that art, literature, poetry, and music express something about our condition in the world, even if only on a subconscious and instinctive level.

***

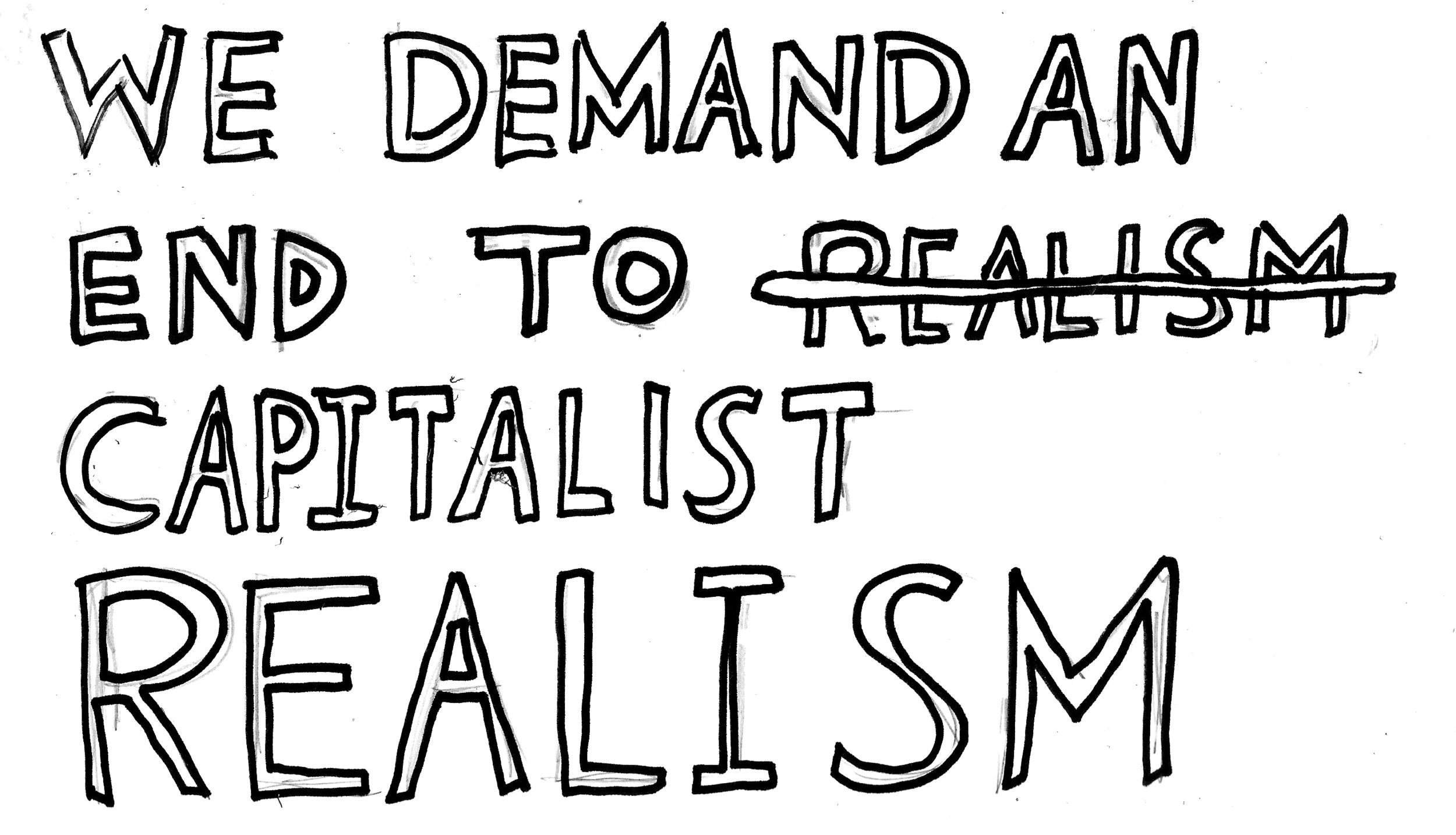

TEN YEARS ago, as the Great Recession ripped through people’s lives, the left-wing cultural critic Mark Fisher penned his book Capitalist Realism. The book diagnosed a cultural logic of late-late-capitalism in which the Thatcherite idea of “There Is No Alternative” had been diffused through every politico-economic institution, every cultural manifestation, how we regard work and education, consumption and self-expression.

A decade later, Fisher is dead. And his gestating manifestoes of Capitalist Realism’s counterpoint and cure, his “Acid Communism,” his belief in the connection between fighting for and imagining a revamped world, remains unfinished.

What then of realism in general? A century ago the idea of realism, of unflinching reflection of reality, still held a radical potentiality. The promise that it might shed light on powerful yet neglected corners of existence. But that potential has been recuperated, sterilized. Any honest assessment has to admit that realism has failed working and oppressed people. It has become a method not of imaginative freedom but of dreary limitations.

Meanwhile, reality seems to have jumped through the looking glass with relish and aplomb. And why not? “The end of civilization” is no longer such an intangible, far off possibility. In the context of that imagination totalizer, why shouldn’t world leaders be engaging in Twitter flame wars? Why shouldn’t pundits drink lightbulb steaks on Fox News to “own the libs”? Why shouldn’t the most bonker-bananas satire have come into actual being?

The default mode of free creativity, therefore, among the post-digital, post-War-on-Terror, post-Great Recession generations, is what we and other radical thinkers call irrealism; a slipstream between the reality of the current moment and the subversive fantastic, using the dark and forgotten corners as a portal between the two.

It is this brand of irrealism that collapses genres and embraces the absurd. It transposes the “real” into the imaginary, and takes as its starting point the possibility of regaining agency, that ordinary people can change the world so long as they can reimagine it.

***

REALISM HAS become a tool of the bourgeoisie. The proofs of its barbarisms, the videos of its police racism, the images of its privations, instead of inciting the masses, now often serve to recapitulate trauma. A realistic image of capitalist barbarism that incited riots three decades ago now functions as a threat and a warning.

The narrative realisms of middle-brow culture and “prestige television” are often elaborate apologetics for complicity. The world is a nightmare – but “what are you gonna do about it anyway?” Tony Soprano, Rick Grimes, Stringer Bell, Walter White – they mostly did their best. They are flawed. But what could they really do? It doesn’t matter how many bodies piled up.

These apologies for everyday horror embody the tropes of mid-century modernism (the alienated modern man) without what made it modernism (the existential wrestling with social morality). This is true even when the subject matter is presented in a speculative manner. Capitalist realism flows through many zombie, science-fiction and fantasy artifacts.

At the same time, we are stymied by an aesthetic and philosophical impasse, what we might call “the impossibility of representation.” Today the artist can no longer claim to authoritatively represent, rightly or wrongly, the subjectivities of the vast and complex exploited and oppressed.

Hence, again, irrealism. Through imagined worlds, we find what the surrealists would have called the dream image, what the Indian artist and communist Anupam Roy calls the “real image,” – and present these recalibrated subjectivities in a differentiated totality (a tapestry of multiple signs that evoke the entirely of the exploited and oppressed).

For example, Anupam presents in one of his paintings, a Venus of Willendorf with her breast cut off; echoing Nangeli – the Dalit woman who cut off her breast in order to pay her taxes. LR editor Adam Turl paints the Willendorf Venus as a transvenus; he uses the hobo warning symbol to foreshadow the protest cry of “hands up don’t shoot.” Or take Mike Linaweaver’s imagery of flags starving at the end of their flagpoles. Or Tish Markley’s opossum memes as assassination devices.

Such work can act as a healing agent. The working-class is traumatized, but the cultural, the dream image and the narrative, act with and against the collective subconscious. The purpose of this healing aspect is the valorization of working-class lives and beings in opposition to capitalism; to be songs to sing on barricades to come.

Capitalist realism flattens history and its cultural artifacts into an apocalyptic time. All of history is, for the bourgeois, treated like a buffet. The capitalist projects a constant and unchanging cynical morality backwards and forwards. Our response is a gothic futurism; a recapitulation of all the lives, past, present, and future, lost to capitalism and its oppressions. In opposition to capitalist apologetics we interweave a working-class morality; a steadfast identification, past and future, with the entirety of the working-class. This does not imply a simplistic class hagiography, rather an identification with the actuality of working-class subjects within irrealism. See, for example, Alexander Billet’s “Flint: Soluble Futures” and Adam Turl and Tish Markley’s Born Again Labor Museum (BALM).

The capitalist realist flattening of time goes in tandem with the slow cancelation of the future. They are already planning the rockets with which they plan to escape the planet they destroyed. They are buying bomb shelters in New Zealand. But still they cut your financial aid, lay you off, raise your rent, deny you health care.

***

OUR IRREALISM must be, at punctuated moments, absurdist. The contemporary invocation of absurdism is an assertion of tricksterism. This is a representation of how a precarious working-class experiences events as cosmic randomness: 9/11 and the “War on Terror”, the economic collapse of 2008, the rise of Trump, the vagaries of online mobs in a world in which every online person has become a public figure, the sudden growth of socialist organization in the U.S., etc. Or, more prosaically, the sudden loss of health insurance, employment, housing, a sudden death at the hands of the police, the sudden demise of a bourgeois politician caught in a pedophilia ring.

In this cosmic random variable lies hope as well as tragedy. The trickster is not good or evil. It is creation and destruction. This is not to say the aforementioned events are truly cosmic or random. They can be explained by Marxism and science. However, they are often experienced in a manner the recalls the randomness of everyday life among our hunting and gathering ancestors.

Our irrealism argues that art is not entertainment. The weak avant-garde, the art world, the mandarins of “serious” literature, have allowed the false idea that art is mere entertainment to flourish. They have done this under a false flag of anti-elitism. But, in truth, they are denying the masses the “deeper” aspects of art. They are talking down to you. They offer you Mountain Dew and giant slides in art museums. This view of art and culture is related to a proprietary view of identity that has been adopted in these bourgeois and petit-bourgeois milieus. The truth is that art is no more mere entertainment than dreams and nightmares are mere sleepy-time television shows.

The collapse of irrealist genres show us that psychological alterity, the narrative otherness of thspeculative, is irrealism’s key feature. The cognitive estrangement of science fiction, its “making weird,” is not due to the scientific aspect of that specific genre. It springs from this alterity in relationship to the horrific realisms of everyday life. In literature – noir, fantasy, science-fiction, horror, all collapse into one long dream. In visual art – conceptualism, total installation, surrealism, abstraction, representation, folk and outsider art, all collapse into another, but related, dream.

The capitalists have created, to replace the social dreamscape of modern art and culture, a digital dreamscape to commodify, map, and reshape our dreams. This “social industry,” as Richard Seymour calls it, displaces the analog culture industry of years past. While the analog culture industry was shaped by capital it was also a site of constant contention. Artists fought over the dream life of the masses. The social industry seeks to wipe out that contestation, while simultaneously promising true democracy. Neither the analog or digital worlds, each controlled by capital, allows for the true expression of the masses and their aspirations for socialism. This is why Locust Review alternates between the digital and analog, as it alternates itself in time, formally and narratively.

Those “socialists” who pretend there is a vast normative working-class are wrong. The working-class is weird. The evoked historical (and partially imaginary) “normal” working-class had less to do with anything inherently proletarian than it did with the persistence of rural and peasant cultures among newly proletarianized workers. The working-class, adrift in a world without sentiment, had to, eventually, make its own sentiments. They did this in pubs, pool halls, dance clubs, cafes, union halls, on street corners and in basements. Irrealism, gothic futurism, Fisher’s Acid Communism; all organically emerge from this constellation of self-expression in the midst of bleak prospects and weaponized hopelessness.

***

SURREALISTS AND Dadaists pulled dreams of freedom out of a world war whose carnage was then unprecedented. The muralists of Latin America put socialism on public walls as authoritarianism gripped half the planet. The Frankfurt School clung to the utopian impulse even as they fled the Holocaust. Existentialists insisted that living as a full human being was still possible after the A-bomb. There was psychedelia in the wake of the Cuban missile crisis and attempts to globalize the police state. Punk and hip-hop were born in the wreckage of recession and Vietnam.

This is our history. Our culture. And we all have a place in the collective hordes to come. But only if we remember them as they came before. And we must remember. To remember, in an age of amnesia, when events are all flattened into each other, is to violate a political biology, to reawaken as something eldritch and yet cosmically sublime, containing within it memories of a future denied. This is our monster – we are all social eldritch gods.

Today our monster wears a yellow vest. It shouts “ga yau” (“add oil”) on the streets of Hong Kong, chants a mix of Spanish and Yiddish in front of ICE concentration camps. Our monster is alive, struggling desperately against the threat that it might not be. Our monster is the only being to inhabit two moments in two different timelines simultaneously.

Locust Review strives to give an imaginative voice to this old-new homunculus of history. It is communist. It is avant-garde. It is non-dogmatic. It is striving to be popular but hated. It is an experiment in human creativity when the means of creation have been transformed more dramatically in the past thirty years than virtually any other time in the history of the species. It is resolute in its refusal to give up the dream of utopia even as the world looks exceedingly grim. It is a deliberate anachronism that holds a future. Perhaps not the future, but a future; a future that redeems the past.

Death to capitalist realism. Long live the radical weird.

Subscribe to Locust Review for as little as $1 a month.

To submit work to Locust Review e-mail us at locust.review@gmail.com.

Social media splash image, Dreams Cum Tru (Born Again Labor Museum) by Adam Turl and Tish Markley